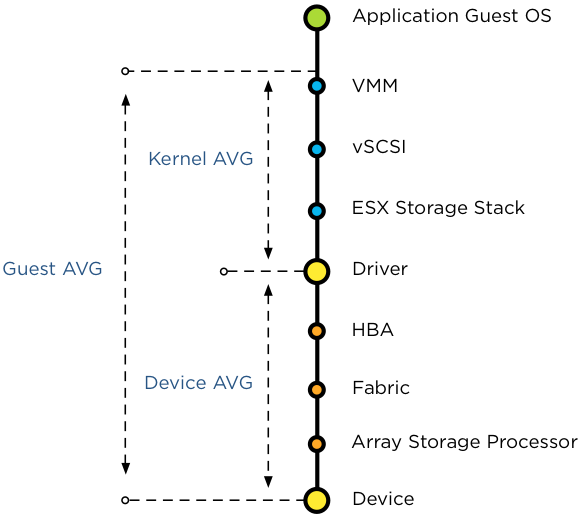

Today someone asked if the congestion threshold of SIOC is related to which host latency threshold? Is it the Device average (DAVG), Kernel Average (KAVG) or Guest Average (GAVG)?

Well actually it’s none of the above. DAVG, KAVG and GAVG are metrics in a host-local centralized scheduler that has complete control over all the requests to the storage system. SIOC main purpose is to manage shared storage resources across ESXi hosts, providing allocation of I/O resources independent of the placement of virtual machines accessing the shared datastore. And because it needs to regulate and prioritize access to shared storage that spans multiple ESXi hosts, the congestion threshold is not measured against a host-side latency metric. But to which metric is it compared? In essence the congestion threshold is compared with the weighted average of D/AVG per host, the weight is the number of IOPS on that host. Let’s expand on this a bit further.

Average I/O latency

To have an indication of the load of the datastore on the array, SIOC uses the average I/O latency detected by each host connected to that datastore. Average latency across hosts is used to cope with the variety of workloads, the characteristic of the active workloads, such as read versus writes, I/O size and degree of sequential I/Os in addition to array behavior such as block location, caching policies and I/O scheduling.

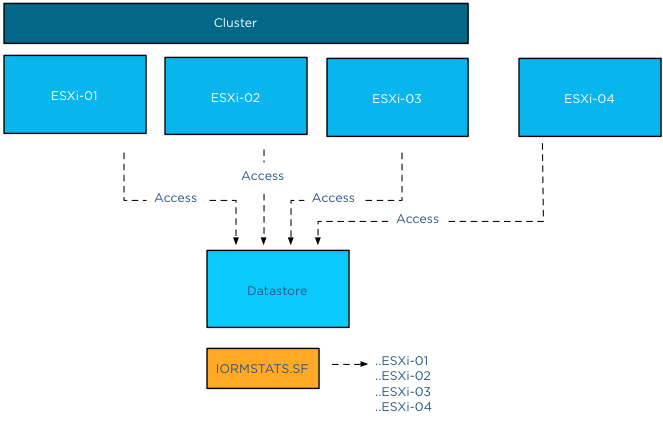

To calculate and normalize the average latency across hosts, each host writes its average device latency and number of I/Os for that datastore in a file called IORMSTATS.SF stored on the same datastore.

A common misconception about SIOC is that it’s compute cluster based. The process of determining the datastore-wide average latency really reveals the key denominator – hosts connected to the datastore – . All hosts connected to the datastore write to the IORMSTATS.SF file, regardless of cluster membership. Other than enabling SIOC, vCenter is not necessary for normal operations. Each connected host reads the IORMSTATS.SF file each 4 seconds and locally computes the datastore-wide average to use for managing the I/O stream. Therefor cluster membership is irrelevant.

Datastore wide normalized I/O latency

Back to the process of computing the datastore wide normalized I/O latency. The average device latencies of each host are normalized by SIOC based on the I/O request size. As mentioned before, not all storage related workloads are the same. Workloads issuing I/Os with a large request size result in longer device latencies due to way storage arrays process these workloads. For example, when using a larger I/O request size such as 256KB, the transfer might be broken up by the storage subsystem into multiple 64KB blocks. This operation can lead to a decline of transfer rate and throughput levels, increasing latency. This allows SIOC to differentiate high device latency from actual I/O congestion at the device itself.

Number of I/O requests complete per second

At this point SIOC has normalized the average latency across hosts based on I/O size, next step is to determine the aggregate number of IOPS accessing the datastore. As each host reports the number of I/O requests complete per second, this metric is used to compare and prioritize the workloads.

I hope this mini-deepdive into the congestion thresholds explains why the congestion threshold could never be solely related to a single host-side metric . Because the datastore-wide average latency is a normalized value, the latency observed of the datastore per individual host may be different than the latency SIOC reports per datastore.

.

Removing the horizontal bar in the footer of a word doc

Now for something completely different, a tip how to extend your life with about 5 years – or how to remove the horizontal bar in the footer of a word document.

Unfortunately I have to deal with the mark-up of word documents quite frequently and am therefor exposed to the somewhat unique abilities of the headers and footers feature of MS-Word. During the edit process of the upcoming book, Word voluntarily added a horizontal bar to my footer. Example depicted below.

However word doesn’t allow you to highlight and select a horizontal bar and therefor cannot be easily removed by pressing the delete button.

This means you have to explore the fantastic menu of word.

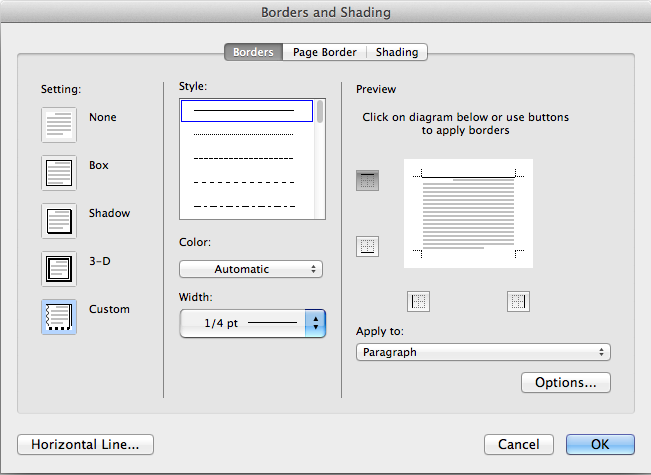

To remove the bar:

1. Open the footers section, by clicking in that area in the document.

2. Go to menu option Format

3. Borders and Shading

4. The borders and shading menu shows the line that miraculous appeared in my footer, by selecting the option None at the right side of the window it removes the horizontal bar from the footer.

5. Click OK

I hope this short tip helps you to keep the frustration to a minimum.

Disabling MinGoodness and CostBenefit

Over the last couple of months I’ve seen recommendations popping up on changing the MinGoodNess and CostBenefit settings to zero on a DRS cluster (KB1017291) . Usually after the maintenance window, when hosts where placed in maintenance mode, the hosts remain unevenly loaded and DRS won’t migrate virtual machines to the less loaded host.

By disabling these adaptive algorithms, DRS to consider every move and the virtual machines will be distributed aggressively across the hosts. Although this sounds very appealing, MinGoodness and CostBenefit calculations are created for a reason. Let’s explore the DRS algorithm and see why this setting should only be used temporarily and not as a permanent setting.

DRS load balance objectives

DRS primary objective is to provide virtual machines their required resources. If the virtual machine is getting the resources it request (dynamic entitlement), than there is no need to find a better spot. If the virtual machines do not get their resources specified in their dynamic entitlement, then DRS will consider moving the virtual machine depending on additional factors.

This means that DRS allow certain situations where the administrator feels like the cluster is unbalanced, such as an uneven virtual machine count on hosts inside the cluster. I’ve seen situations where one host was running 80% of the load while the other hosts where running a couple of virtual machines. This particular cluster was comprised of big hosts, each containing 1TB memory while the entire virtual machine memory footprint was no more than 800GB. One host could easily run all virtual machines and provide the resources the virtual machines were requesting.

This particular scenario describes the biggest misunderstanding of DRS, DRS is not primarily designed to equally distribute virtual machines across hosts in the cluster. It distributes the load as efficient as possible across the resources to provide the best performance of the virtual machines. And this is the key to understand why DRS does or does not generate migration recommendation. Efficiency! To move virtual machines around, it cost CPU cycles, memory resources and to a smaller extent datastore operation (stun/unstun) virtual machines. In the most extreme case possible, load balancing itself can be a danger to the performance of virtual machines by withholding resources from the virtual machines, by using it to move virtual machines. This is worst-case scenario, but the main point is that the load balancing process cost resources that could also be used by virtual machines providing their services, which is the primary reason the virtual infrastructure is created for. To manage and contain the resource consumption of load balancing operations, MinGoodness and CostBenefit calculations were created.

CostBenefit

DRS calculates the Cost Benefit (and risk) of a move. Cost: How many resources does it take to move a virtual machine by vMotion? A virtual machine that is constantly updating its large memory footprint cost more CPU cycles and network traffic than a virtual machine with a medium memory footprint that is idling for a while. Benefit: how many resources will it free up on the source host and what will the impact be on the normalized entitlement on the destination host? The normalized entitlement is the sum of dynamic entitlement of all the virtual machines running on that host divided by the capacity of the host. Risk is predicted how the workload might change on both the source and destination host and if the outcome of the move of the candidate virtual machine is still positive when the workload changes.

MinGoodness

To understand which host the virtual machine must move to, DRS uses the normalized entitlement of the host as the key metric and will only consider hosts that have a lower normalized entitlement than the source host. MinGoodness helps DRS understand what effect the move has on the overall cluster imbalance.

DRS awards every move a CostBenefit and MinGoodness rating and these are linked together. DRS will only recommend a move with a negative CostBenefit rating if the move has a highly positive MinGoodness rating. Due to the metrics used, CostBenefit ratings are usually more conservative than the MinGoodness ratings. Overpowering the decision to move virtual machine to host with a lower normalized entitlement due to the cost involved or risk of that particular move.

When MinGoodness and CostBenefit are set to zero, DRS calculates the cluster imbalance and recommend any move* that increases the balance of the normalized entitlement of each host within the cluster without considering the resource cost involved. In oversized environments, where resource supply is abundant, setting these options temporarily should not create a problem. In environments where resource demand rivals resource supply, setting these options can create resource starvation.

*The number of recommendations are limited to the MaxMovesPerHost calculation. This article contains more information about MaxMovesPerHost.

Recommendation

My recommendation is to use this advanced option sparingly, when host-load is extremely unbalanced and DRS does not provide any migration recommendation. Typically when the hosts in the cluster were placed in maintenance mode. Permanently activating this advanced option is similar to lobotomizing the DRS load balancing algorithm, this can do more harm in the long run as you might see virtual machines in an almost-constant state of vMotion.

Limiting the number of Storage vMotions

When enabling datastore maintenance mode, Storage DRS will move virtual machines out of the datastore as fast as it can. The number of virtual machines that can be migrated in or out of a datastore is 8. This is related to the concurrent migration limits of hosts, network and datastores. To manage and limit the number of concurrent migrations, either by vMotion or Storage vMotion, a cost and limit factor is applied. Although the term limit is used, a better description of limit is maximum cost.

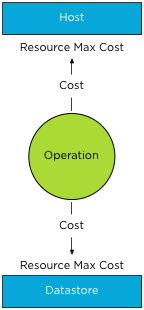

In order for a migration operation to be able to start, the cost cannot exceed the max cost (limit). A vMotion and Storage vMotion are considered operations. The ESXi host, network and datastore are considered resources. A resource has both a max cost and an in-use cost. When an operation is started, the in-use cost and the new operation cost cannot exceed the max cost.

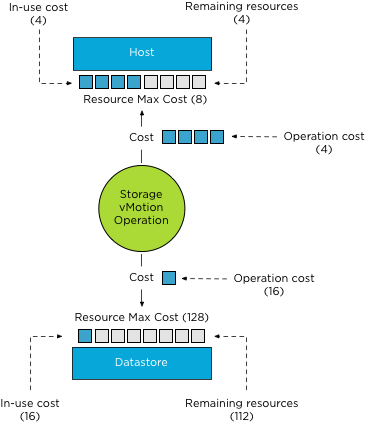

The operation cost of a storage vMotion on a host is “4”, the max cost of a host is “8”. If one Storage vMotion operation is running, the in-use cost of the host resource is “4”, allowing one more Storage vMotion process to start without exceeding the host limit.

As a storage vMotion operation also hits the storage resource cost, the max cost and

in-use cost of the datastore needs to be factored in as well. The operation cost of a Storage vMotion for datastores is set to 16, the max cost of a datastore is 128. This means that 8 concurrent Storage vMotion operations can be executed on a datastore. These operations can be started on multiple hosts, not more than 2 storage vMotion from the same host due to the max cost of a Storage vMotion operation on the host level.

How to throttle the number of Storage vMotion operations?

To throttle the number of storage vMotion operations to reduce the IO hit on a datastore during maintenance mode, it preferable to reduce the max cost for provisioning operations to the datastore. Adjusting host costs is strongly discouraged. Host costs are defined as they are due to host resource limitation issues, adjusting host costs can impact other host functionality, unrelated to vMotion or Storage vMotion processes.

Adjusting the max cost per datastore can be done by editing the vpxd.cfg or via the advanced settings of the vCenter Server Settings in the administration view.

If done via the vpxd.cfg, the value vpxd.ResourceManager.MaxCostPerEsx41Ds is added as follows:

< config >

< vpxd >

< ResourceManager >

< MaxCostPerEsx41Ds > new value < /MaxCostPerEsx41Ds >

< /ResourceManager >

< /vpxd >

< /config >

As the max cost have not been increased since ESX 4.1, the value-name

Please remember to leave some room for vMotion when resizing the max cost of a datastore. The vMotion process has a datastore cost as well. During the stun/unstun of a virtual machine the vMotion process hits the datastore, the cost involved in this process is 1.

For example, Changing the

Please note that cost and max values are applied to each migration process, impact normal day to day DRS and Storage DRS load balancing operations as well as the manual vMotion and Storage vMotion operations occuring in the virtual infrastructure managed by the vCenter server.

As mentioned before adjusting the cost at the host side can be tricky as the costs of operation and limits are relative to each other and can even harm other host processes unrelated to migration processes. If you still have the urge to change the cost on the host, consider the impact on DRS! When increasing the cost of a Storage vMotion operation on the host, the available “slots” for vMotion operations are reduced. This might impact DRS load balancing efficiency when a storage vMotion process is active and should be avoided at all times.

Get notification of these blogs postings and more DRS and Storage DRS information by following me on Twitter: @frankdenneman

Fab-four: VMWorld 2012 sessions approved

This morning I found out that my four sessions are accepted. I’m really pleased and I am looking forward to presenting at each one of them. Two sessions, Architecting Storage DRS Datastore Clusters and vSphere Cluster Resource Pool Best Practices are also scheduled for VMWorld Barcelona.

Session ID: STO1545

Session Title: Architecting Storage DRS Datastore Clusters

Track: Infrastructure

Presenting at: US and Barcelona

Presenting with: Valentin Hamburger

Session ID: VSP1504

Session Title: Ask the Expert vBloggers

Track: Infrastructure

Presenting at: US

Presenting with: Duncan Epping, Scott Lowe, Rick Scherer and Chad Sakac

Session ID: VSP1683

Session Title: vSphere Cluster Resource Pools Best Practices

Track: Infrastructure

Presenting at: US and Barcelona

Presenting with Rawlinson Rivera

Session ID: CSM1167

Session Title: Architecting for vCloud Allocation Models

Track: Operations

Presenting at: US

Presenting with Chris Colotti

Can’t wait to attend VMworld 2012! See you there.